Magnificent essay reblogged from Hack the Cover — by Craig Mod.

Excerpt

……………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Hack the Cover

Covers, covers — everywhere

Muerto!

The covers are dead!

Dead!

Dead like the record jacket!

Dead like the laser disc sleeve!

Dead like the 8-track cartridge sticker!

Dead like the squishy Disney VHS container!

Dead like the cassette case inserts!

Dead like those damned CD jewel cases and their booklets!

Dead like DVD and Blue-ray box art!

Put ’em all in a box, burn ’em, and sprinkle their ashes over your razed local bookstore. Call it a day. Hang up your exact-o knifes and weld shut your drawers of metal type. The writing’s not on the wall but it was on one of those covers you just lit on fire — so we’ll never know what it said.

Next!

OK — phew. Still here? Great.

If digital covers as we know them are so ‘dead,’ why do we hold them so gingerly? Treat them like print covers? We can’t hurt them. They’re dead. So let’s start hacking. Pull them apart, cut them into bits and see what we come up with.

This is an essay for book lovers and designers curious about where the cover has been, where it’s going, and what the ethos of covers means for digital book design. It’s for those of us dissatisfied with thoughtlessly transferring print assets to digital and closing our eyes.

The cover as we know it really is — gasp — ‘dead.’ But it’s dead because the way we touch digital books is different than the way we touch physical books. And once you acknowledge that, useful corollaries emerge.

Leather-bound

Paula Fox writes in her memoir, The Coldest Winter: “I touched his signature as though it had been his face.”1 It’s this kind of intimacy with which we touch physical books, too.

And so we don’t want the cover to disappear. And yet the cover as we have known it is disappearing, rather quickly (nearly eradicated on hardware Kindles). This doesn’t mean it won’t be replaced. Whatever it’s replaced with, however, will not serve the same purpose as the covers with which we’ve grown up.

This romanticism is curious, if only because the cover of whose loss we lament is a recent invention. Matthew Battles writes in his book, Library: An Unquiet History:

“The people who shelve the books in Widener talk about the library’s breathing—at the start of the term, the stacks exhale books in great swirling clouds; at end of term, the library inhales, and the books fly back.”2

I can’t help but imagine all these flying books as leather bound. Thick, dusty, uniform and effectively ‘coverless’ by modern standards. Place them face-up on a table and they look identical: shielded and important but also anonymous. Only the scuffs and wear in the leather tell a story. And that story doesn’t say much about what’s inside.

Here, the cover is a protector of the signatures and the binding. It allows the books to fly in and out of the stacks a thousand times, and still be usable. In the digital world, our books are protected by ubiquity. They are everywhere and nowhere. They multiply effortlessly and can fly continuously without damage or rot. They don’t need covers like printed book need covers.

Kinokuniya & Delight

My awareness and relationship with covers began nearly a decade ago.

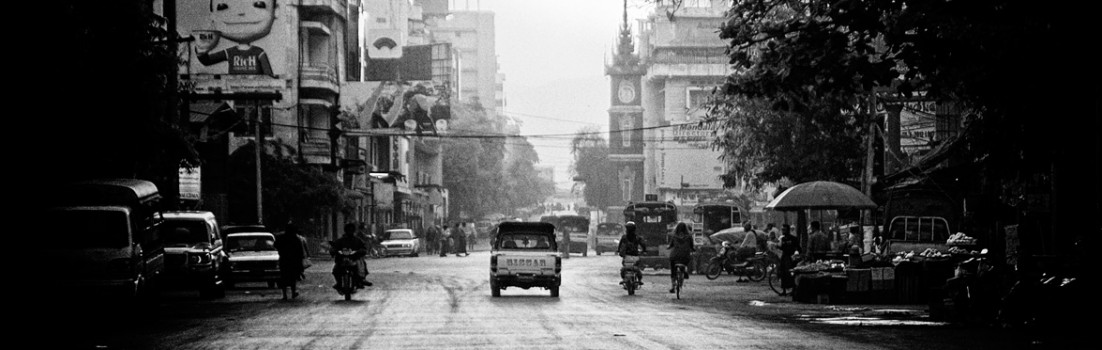

I was nineteen when I walked into Kinokuniya on the east side of Shinjuku station. At the time I knew nothing about Japan or making books. It was my first visit to a Japanese bookstore and, like most of my experiences then with things Japanese, I was amused, full of curiosity, and inspired. The place was bathed in a typically drab and corporate Japanese fluorescence, but drabness be damned, I distinctly recall the delight felt from picking up books at random. They were all so … rational.3

It wouldn’t be until years later that I realized this sense of rationality stemmed from a respect for readers. The books were sized perfectly for your back pocket or bag. Giant volumes were split into smaller tomes. The paper was elegant. The binding strong. Bookmarks glued in. But looking back, I was struck most of all by the austere covers. Little Hara Kenyas everywhere. Expanses of whitespace splashed with well considered marks of ink. One color. Restrained photography. Pretty books. Lots of ’em.4

There were racks of these minimal bricks. In fact, the vast majority fell under this careful aesthetic. In aggregate, this aesthetic formed a unified cultural voice. A rational system. The impact of this experience has stuck with me this past decade and deeply informed all of my design work. I continually ask myself: “How does one develop a design language or ecosystem that tempers itself? That somehow keeps from spiraling out of control?”

Seeing this shed new light on book covers in the west. In contrast, the shelves of our bookstores seemed — and seem — far more chaotic. And as you trace back through the history of the cover, there’s a sense that it’s getting visually louder.

It’s unsurprising, really. There are fewer bookstores. Less shelves. And therefore more competition around attention. This results in an ever escalating shouting match between covers. But with the present digital inflection, the role of the cover is changing radically; disappearing in some cases. It doesn’t need to shout anymore because it doesn’t serve the same purpose.

This shift presents a wonderful chance for designers to break from thinking of a cover as an individual asset, and certainly a chance to break from a tight coupling with the marketing department. In a sense, it’s a chance to play again. To hack. And I can’t help but feel that elements of the design of our future digital books should take to heart the craftsmanship and metered rationality embedded in so much Japanese book design.

Recent Covers

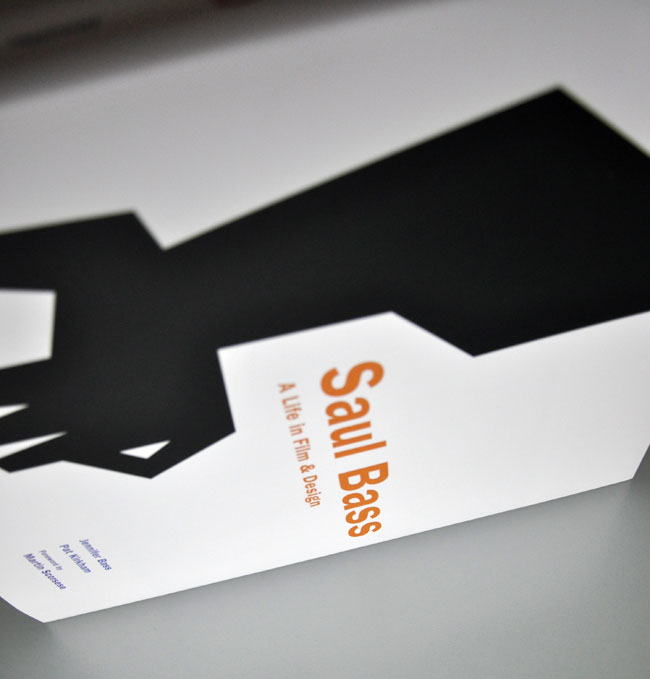

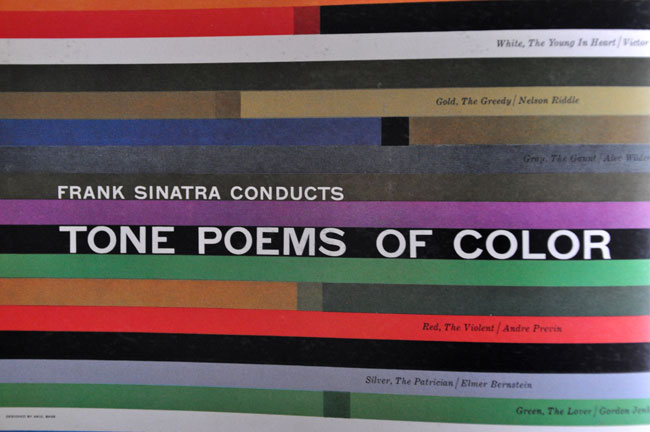

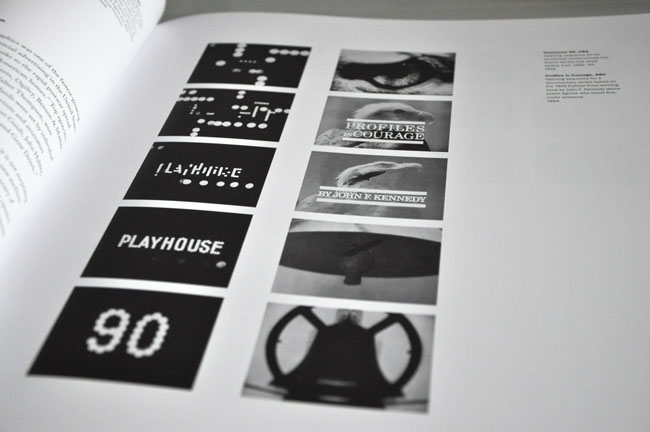

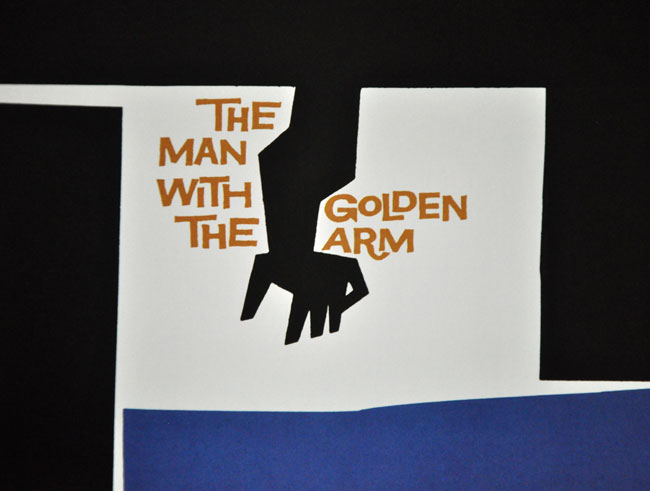

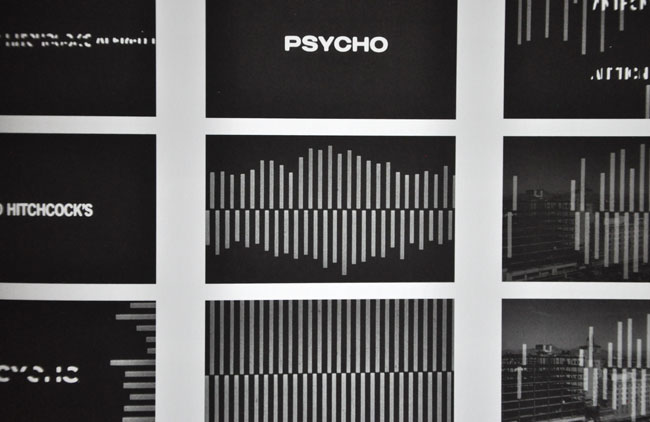

Of course, not all western covers shout. In fact, the past few decades have sheltered some astounding work. The iconic compositions of Chip Kidd, the art direction of John Gall, the illustrative touches of Grey318 or Ben Wiseman, the classic typography of Birdsall, and David Pearson’s and Peter Mendelsund’s beautiful series design.

These designers find ways to make exciting — through illustration or creative debossings or other hacks — a space that’s remained largely unchanged for a hundred years. Their covers occupy a point of convergence blending austerity, sensitivity, reverence for the text and, of course, marketing:5

But covers like this are the exception.

Which begs the question — if so much of what book cover design has evolved into is largely a brick-and-mortar marketing tool, then what place does a ‘cover’ hold in digital books? Especially after you purchase it? But, more tellingly, even before you purchase it?

(…)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Read full essay Hack the Cover — by Craig Mod.